Cancer

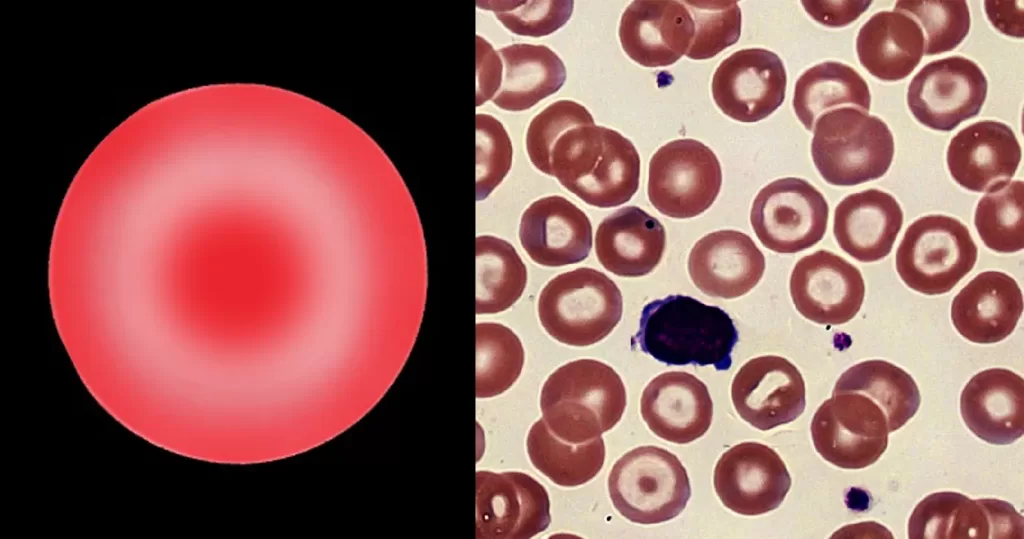

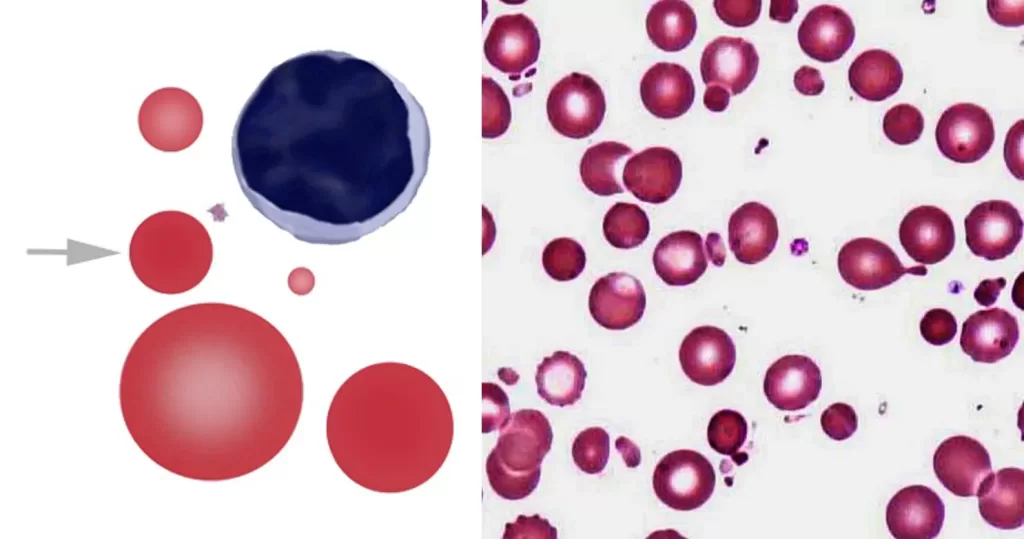

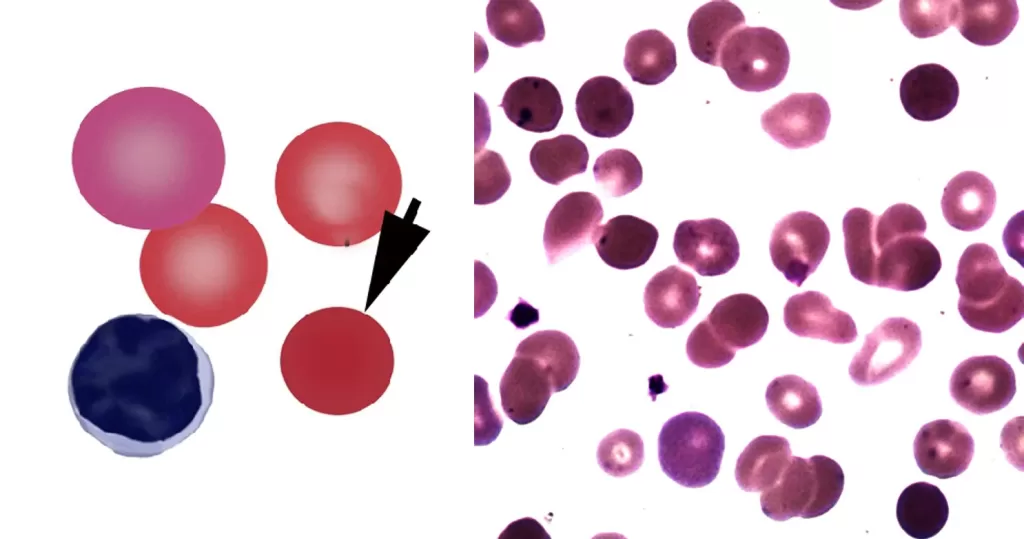

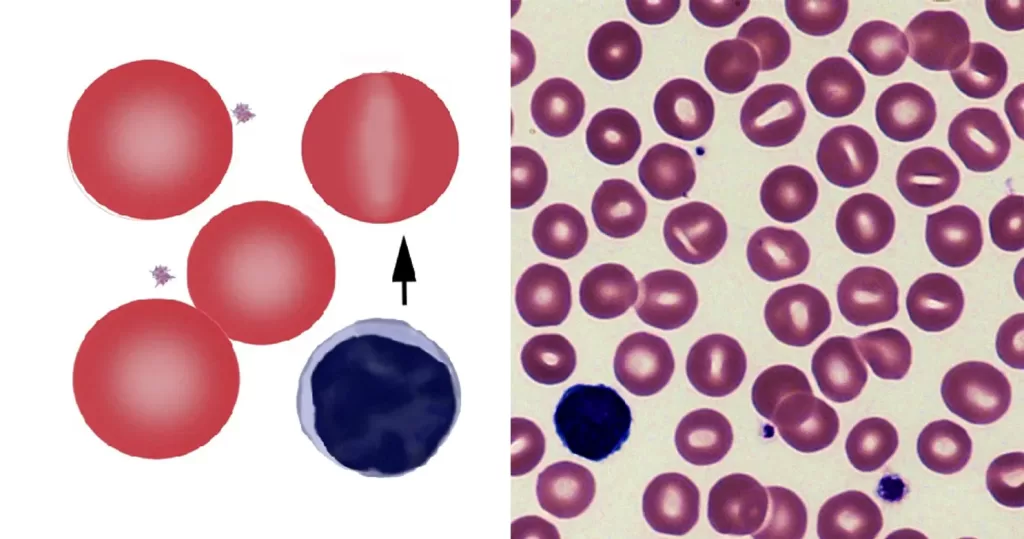

Cancer (medical term: malignant neoplasm is a class of diseases in which a group of cells display uncontrolled growth division beyond the normal limits), invasion (intrusion on and destruction of adjacent tissues), and sometimes metastasis (spread to other locations in the body via lymph or blood). These three malignant properties of cancers differentiate them from benign tumors, which are self-limited, and do not invade or metastasize. Most cancers form a tumor but some, like leukemia, do not. The branch of medicine concerned with the study, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cancer is oncology.

Cancer affects people at all ages with the risk for most types increasing with age. Cancer caused about 13% of all human deaths in 2007 (7.6 million).

Classification

Further information: List of cancer types

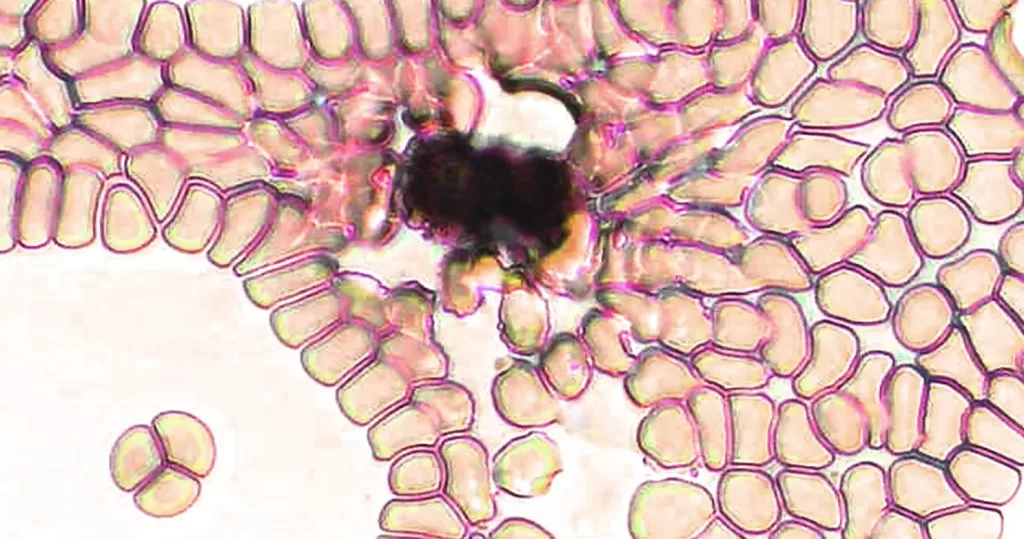

Cancers are classified by the type of cell that resembles the tumor and, therefore, the tissue presumed to be the origin of the tumor. These are the histology and the location, respectively. Examples of general categories include:

- Carcinoma: Malignant tumors derived from epithelial cells. This group represents the most common cancers, including the common forms of breast, prostate, lung and colon cancer.

- Sarcoma: Malignant tumors derived from connective tissue, or mesenchymal cells.

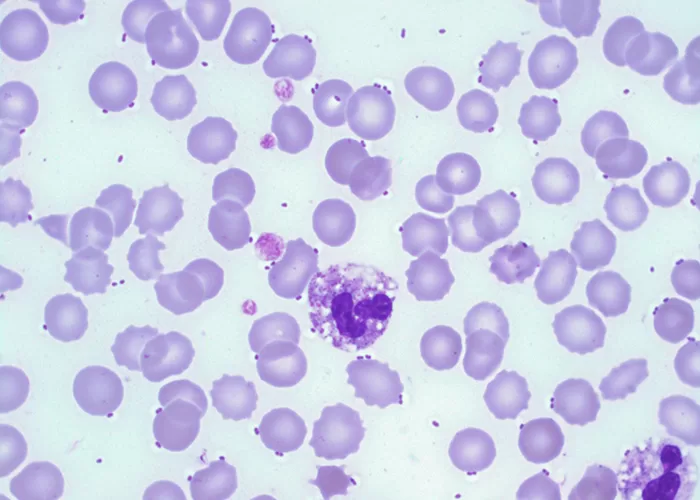

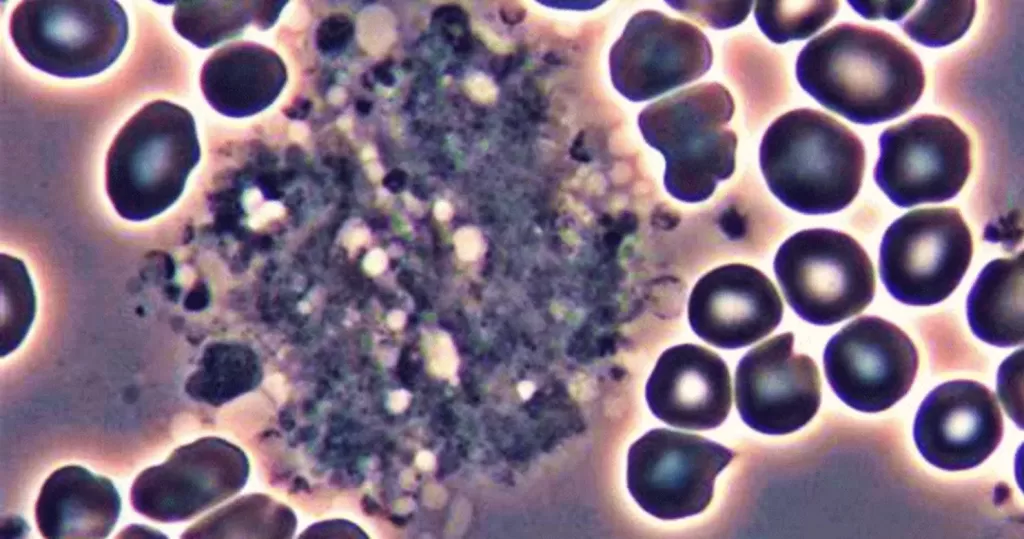

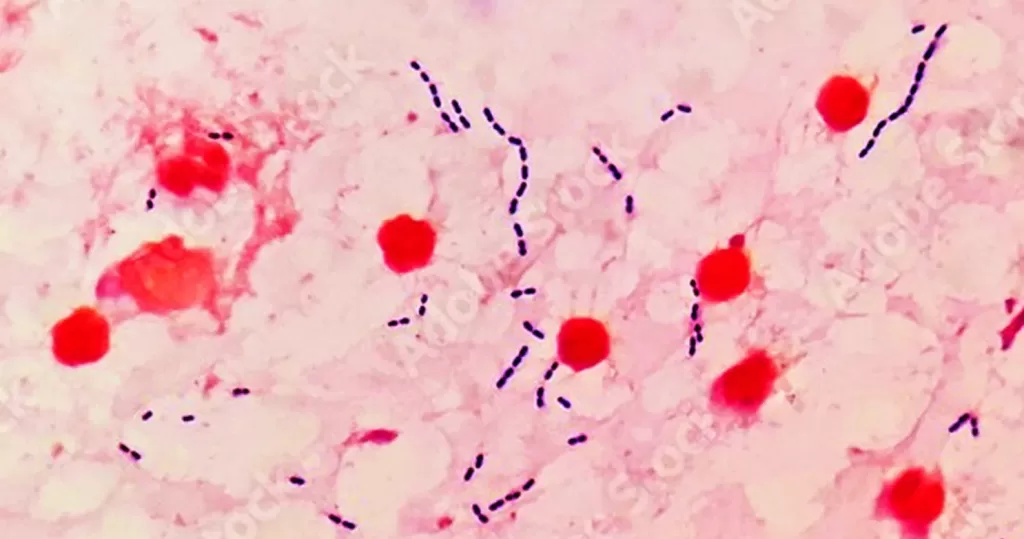

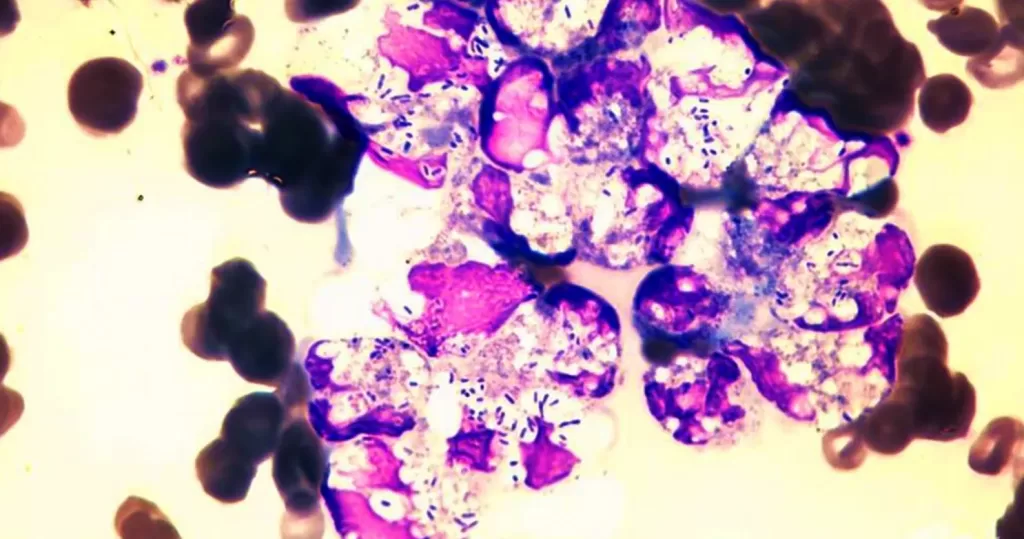

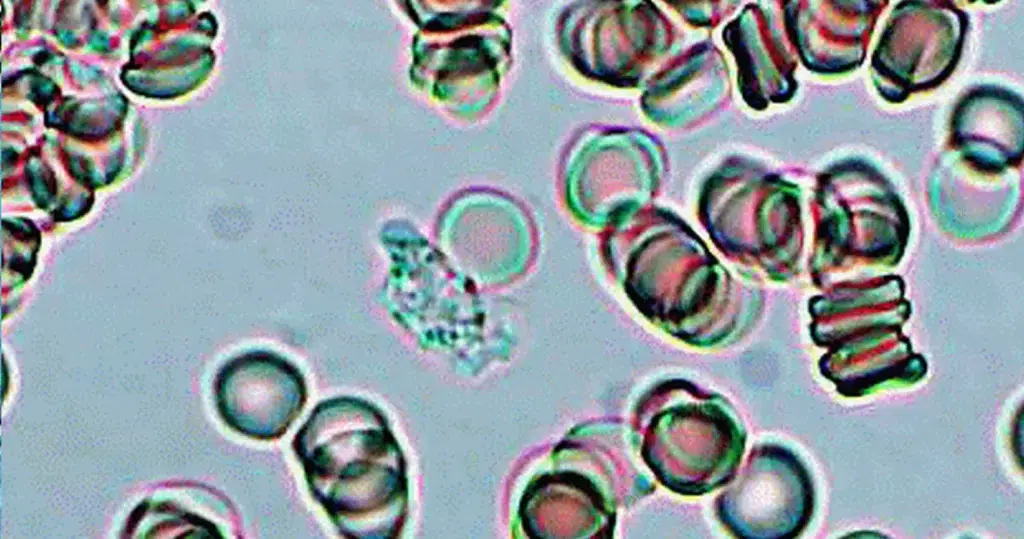

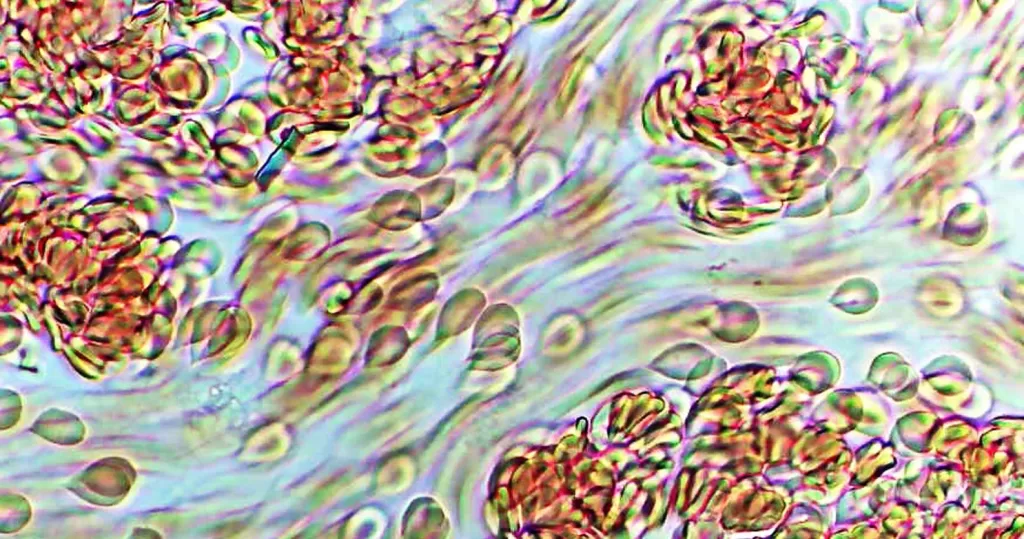

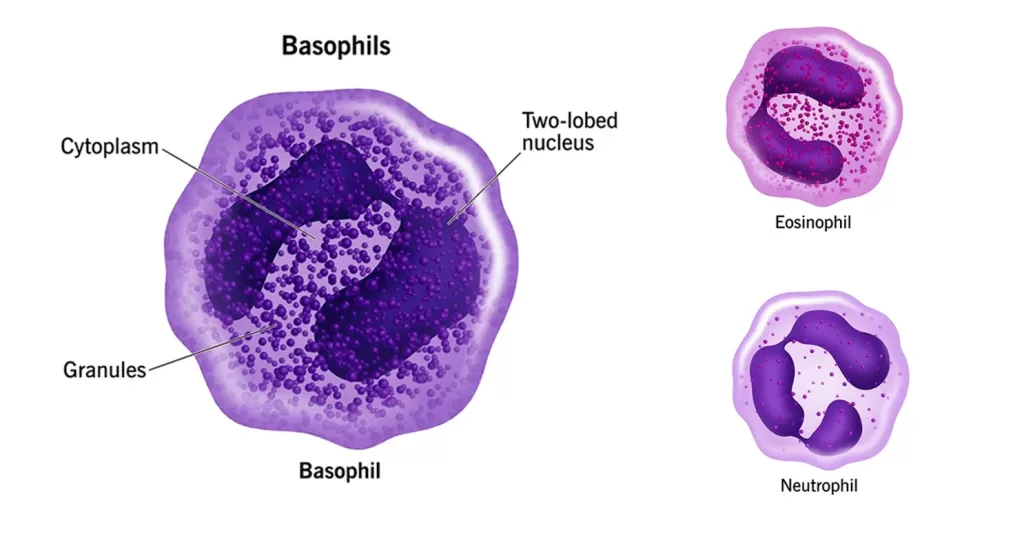

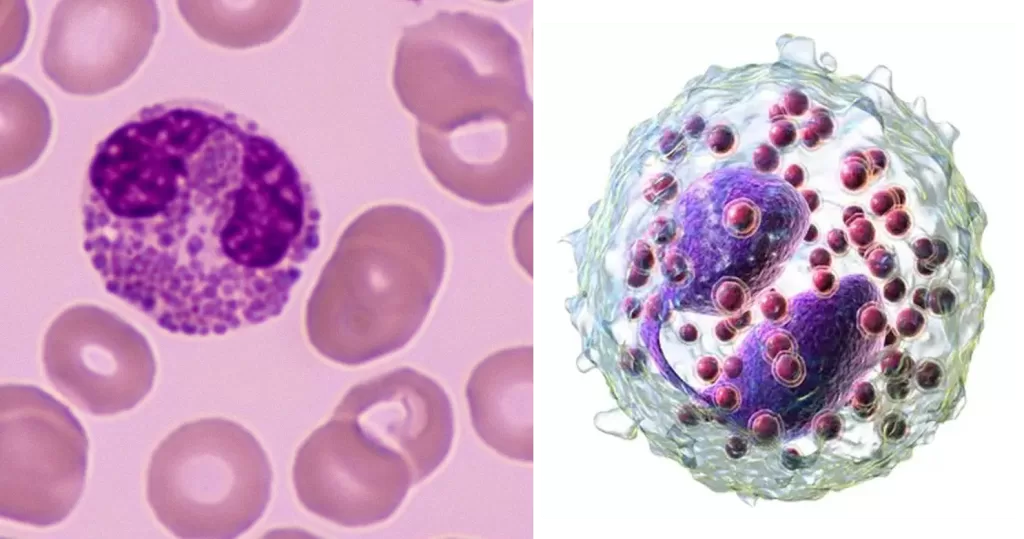

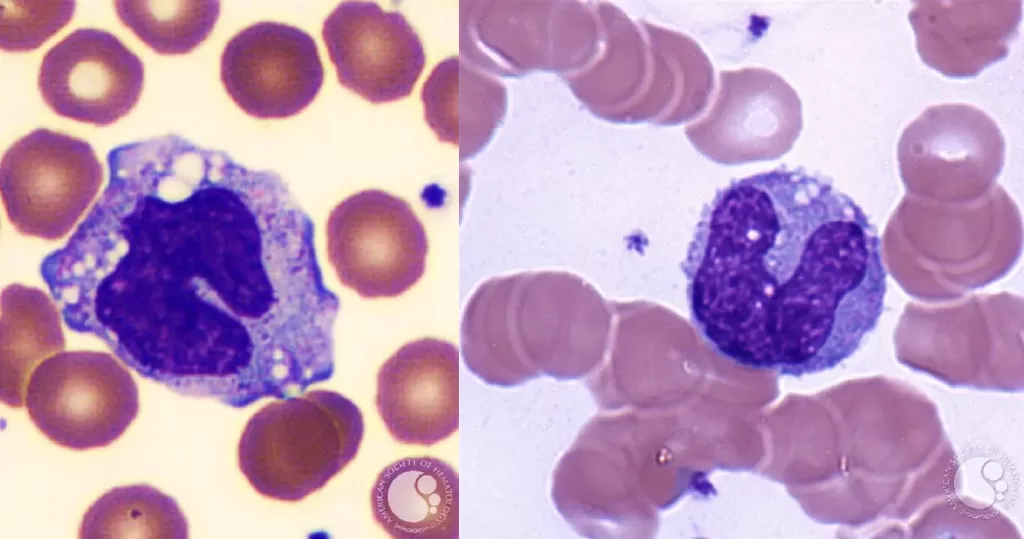

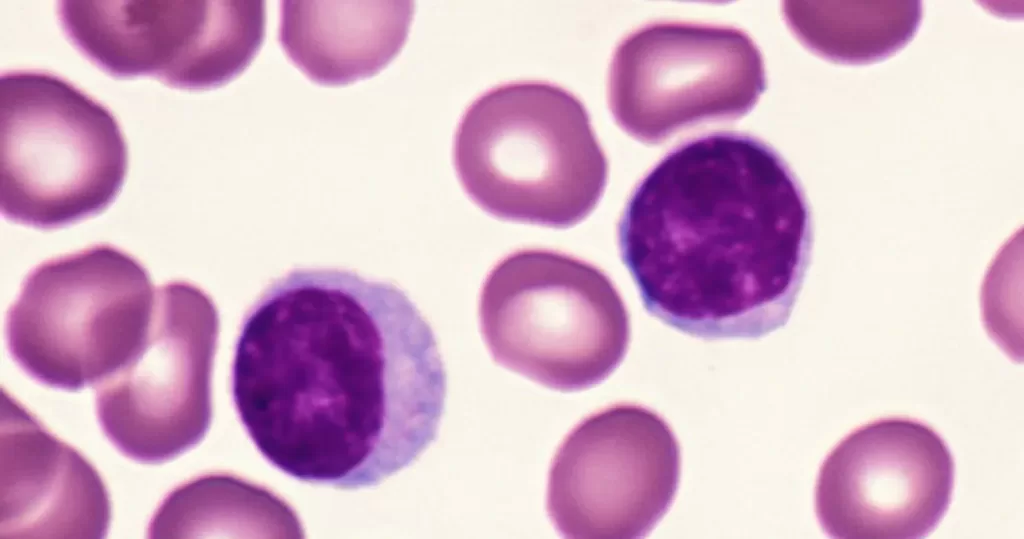

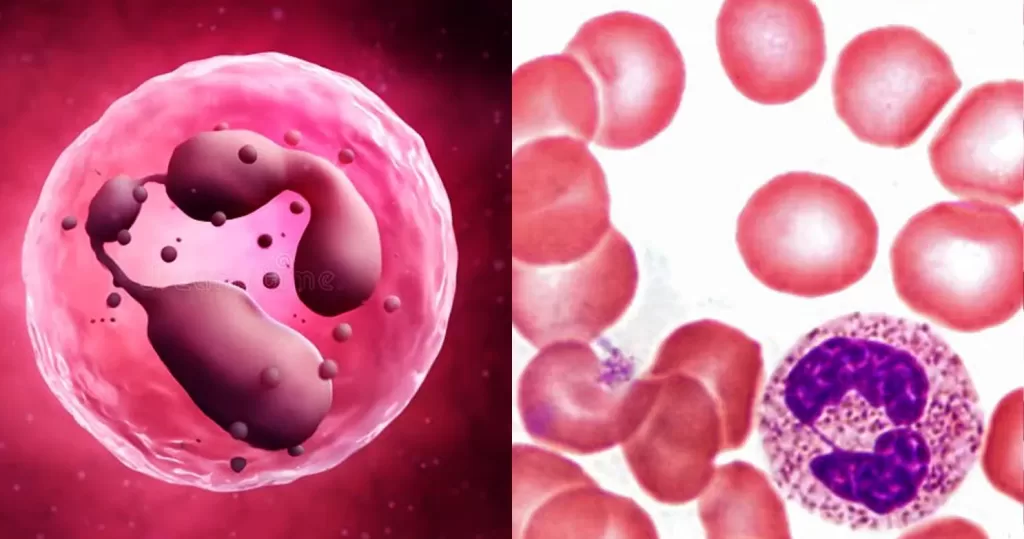

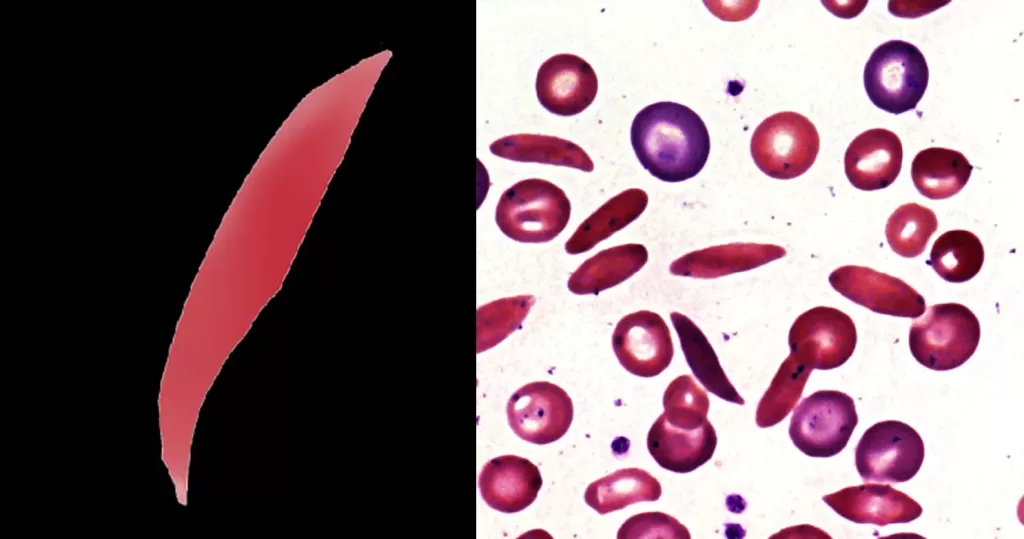

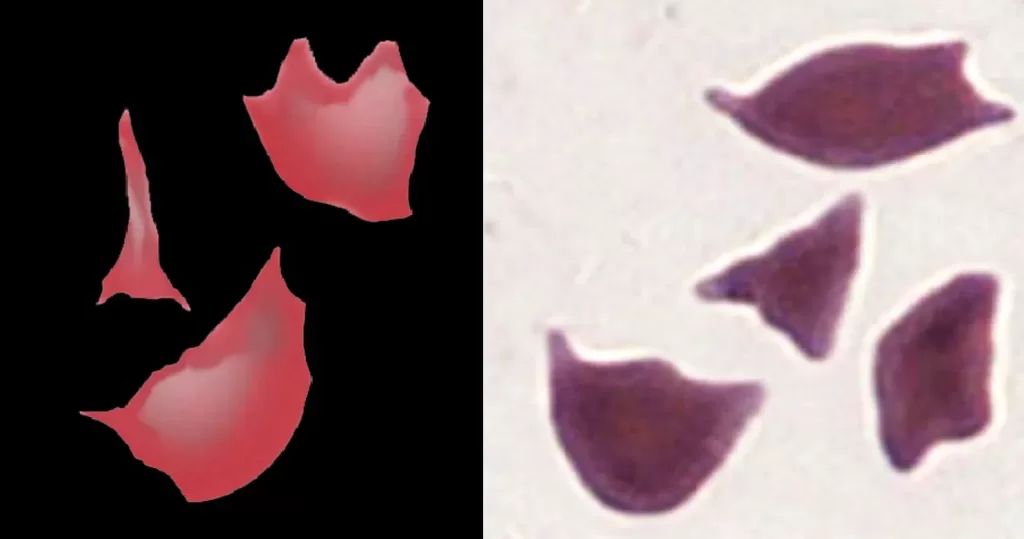

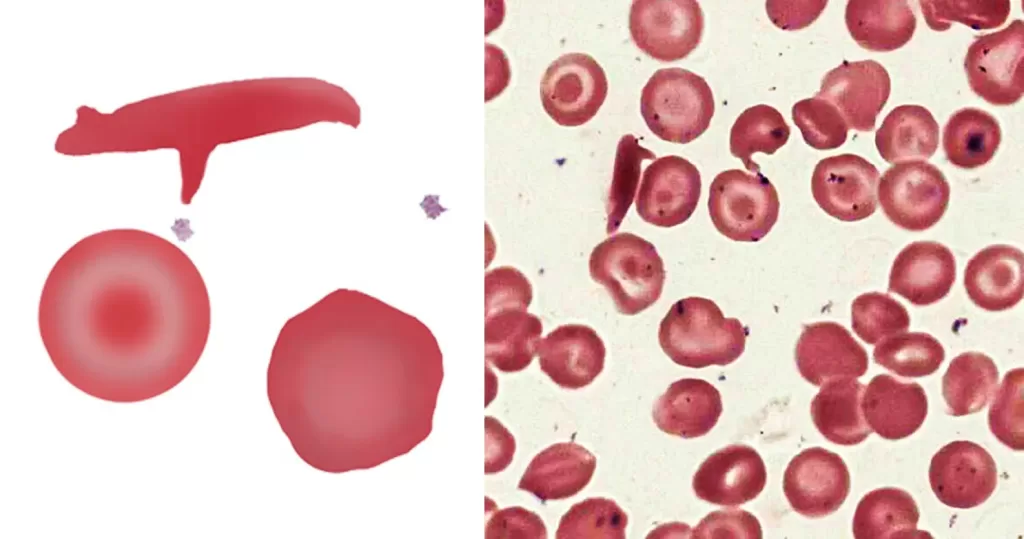

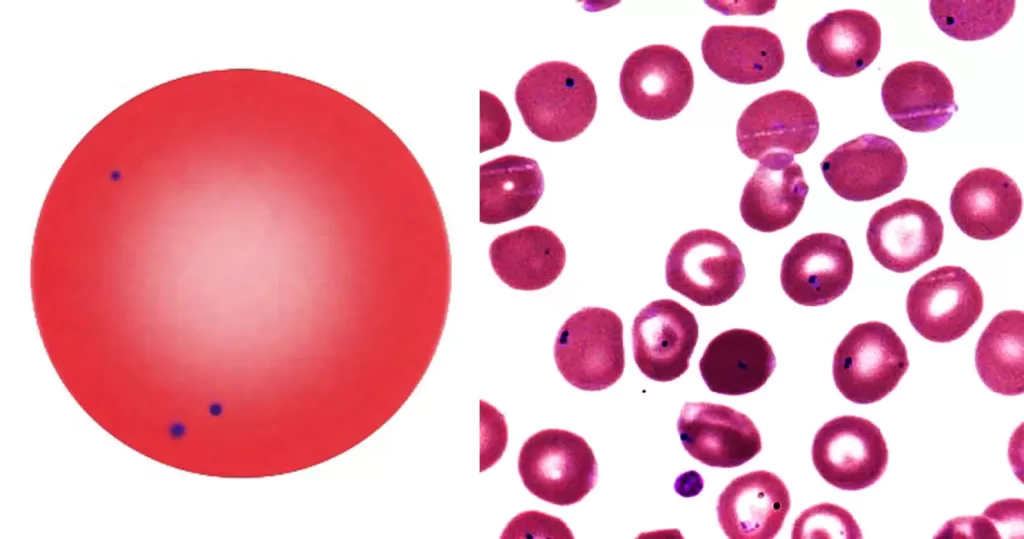

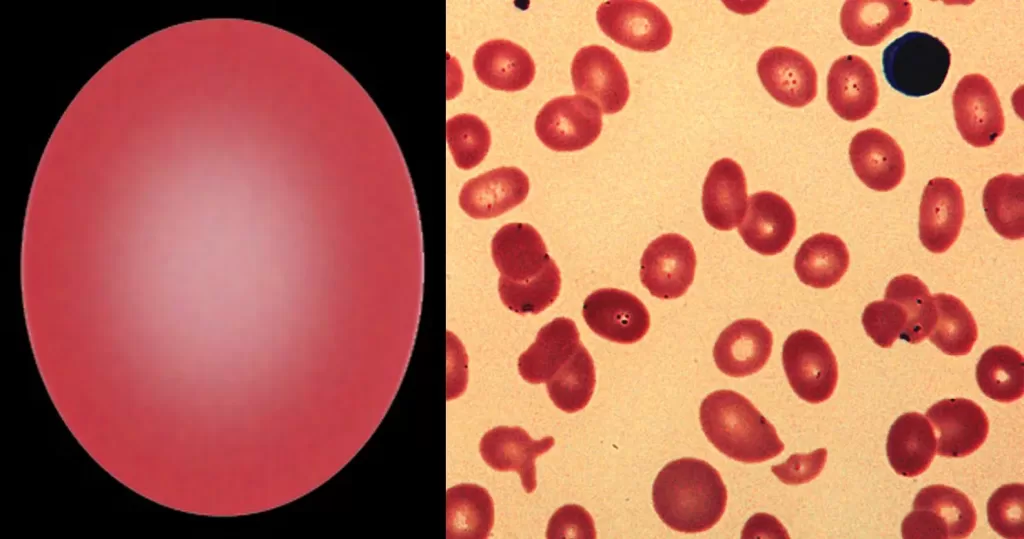

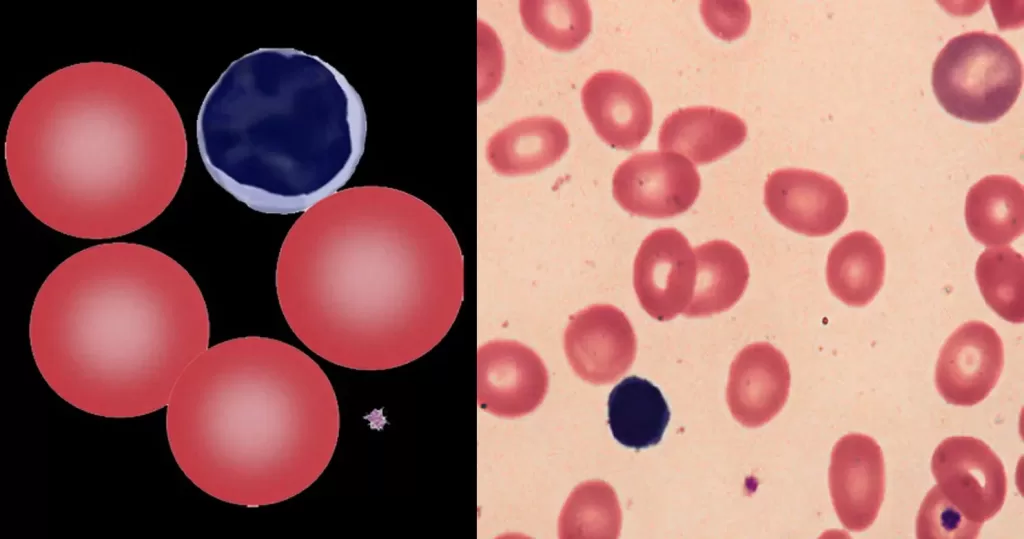

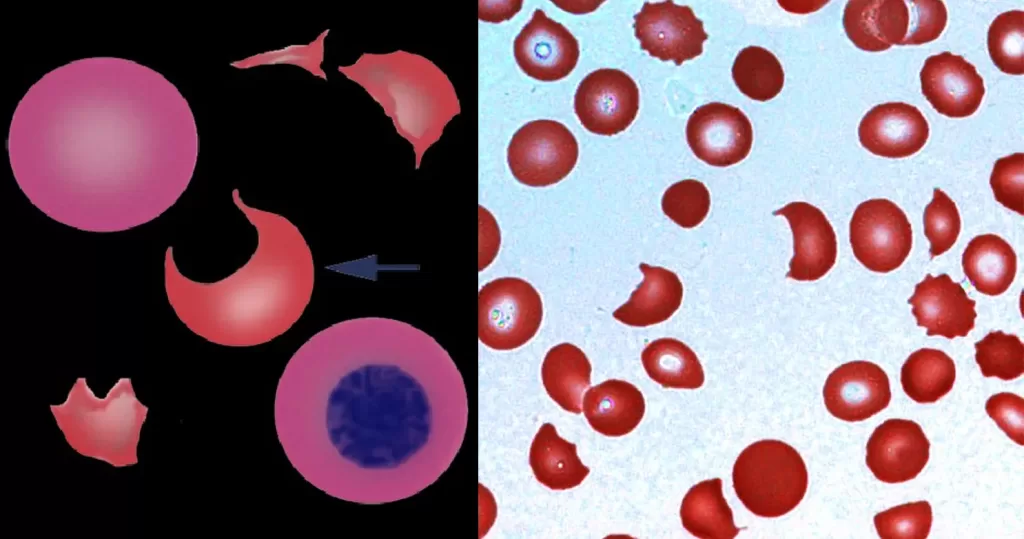

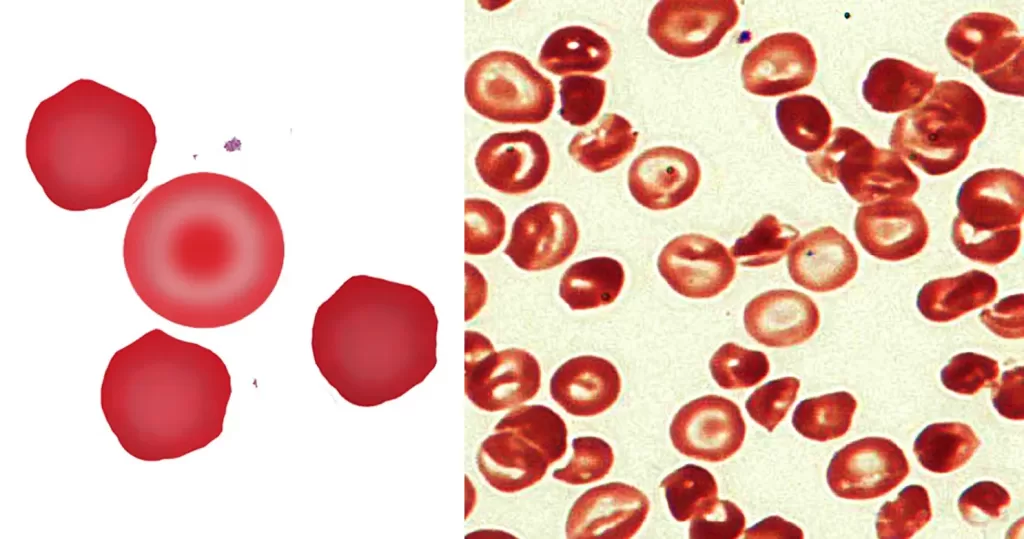

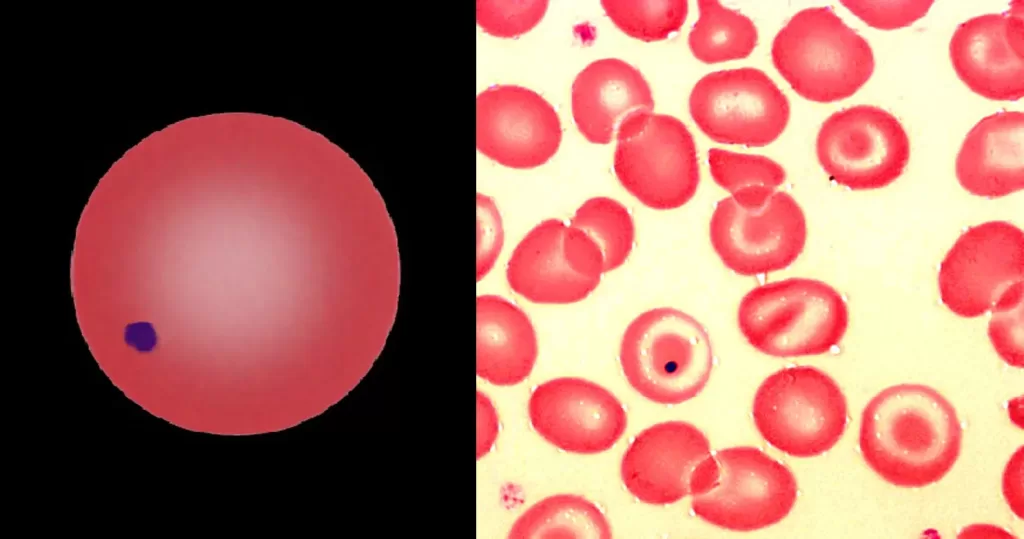

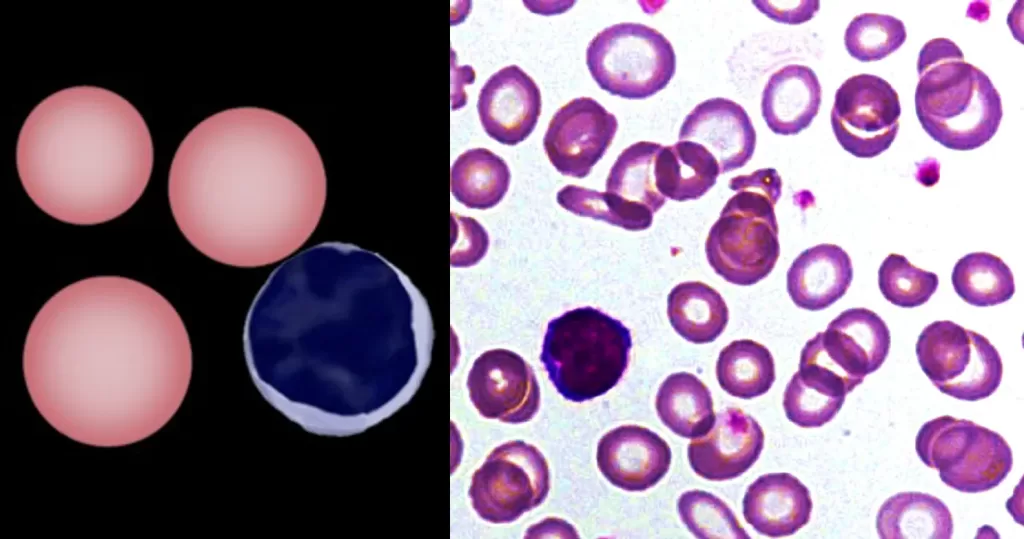

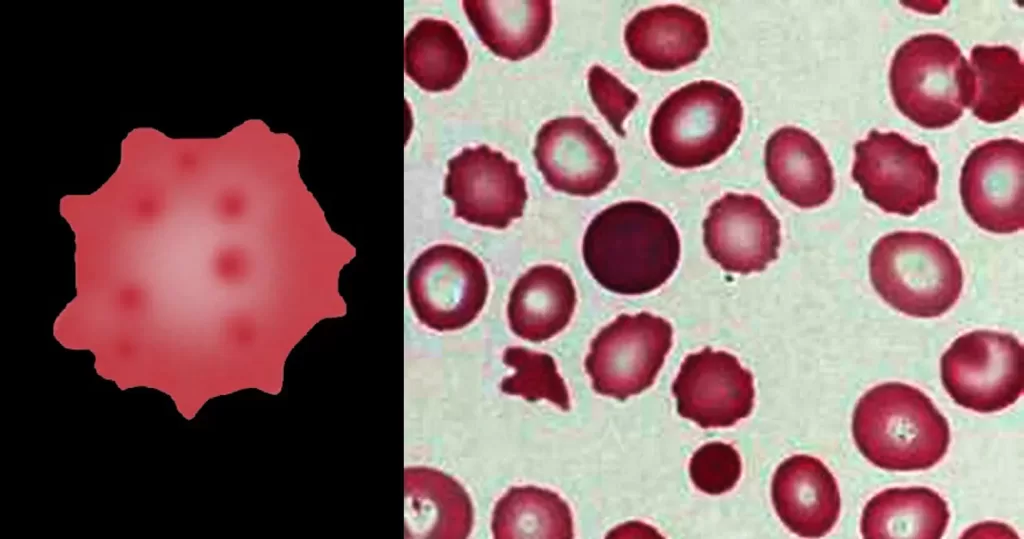

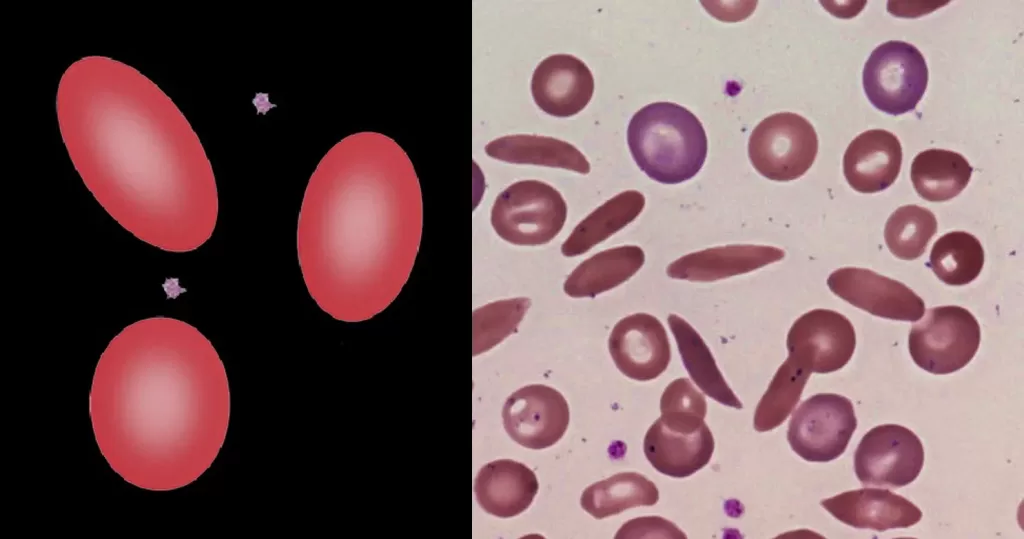

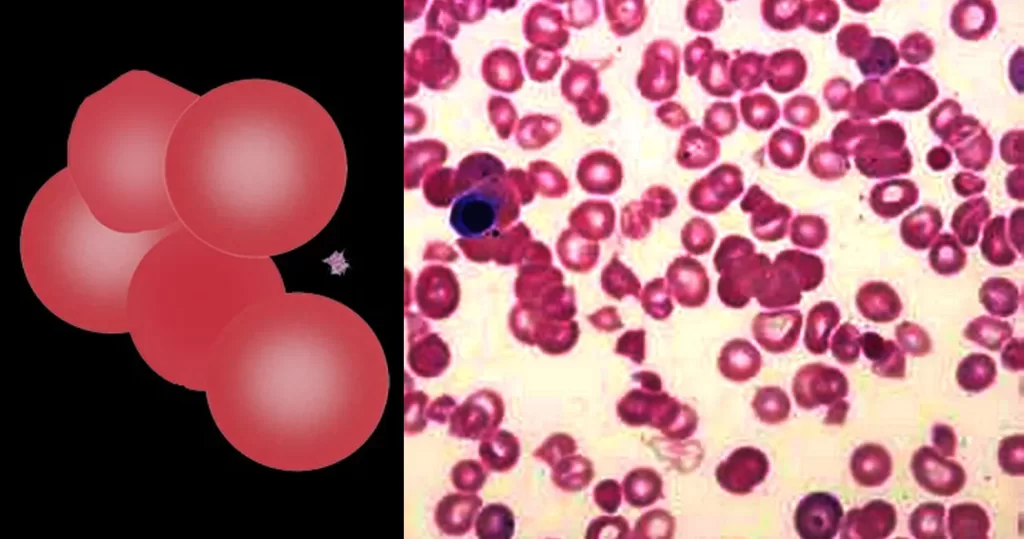

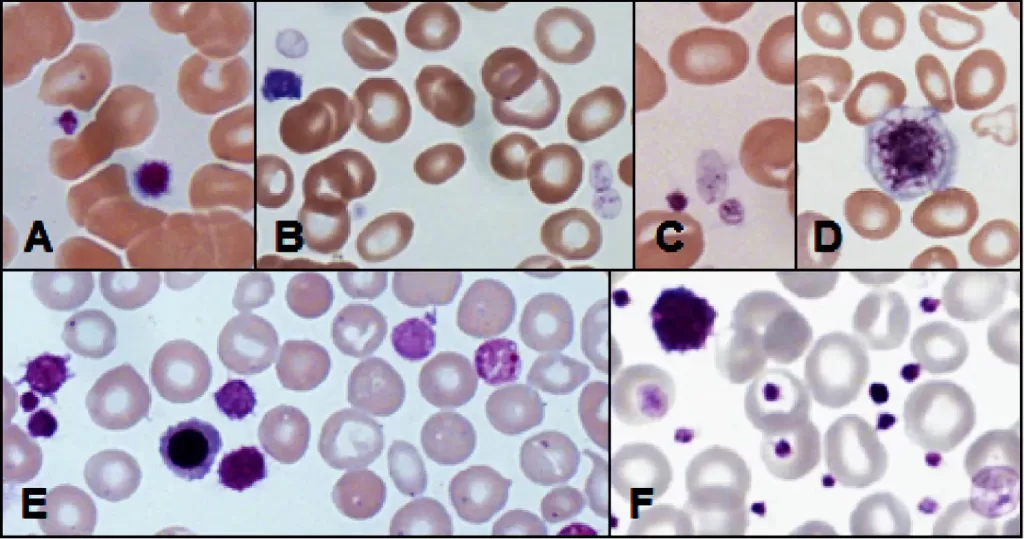

- Lymphoma and leukemia: Malignancies derived from hematopoietic blood-forming cells

- Germ cell tumor: Tumors derived from totipotent cells. In adults most often found in the testicle and ovary; in fetuses, babies, and young children most often found on the body midline, particularly at the tip of the tailbone; in horses most often found at the poll (base of the skull).

- Blastic tumor or blastoma: A tumor (usually malignant) which resembles an immature or embryonic tissue. Many of these tumors are most common in children.

Malignant tumors (cancers) are usually named using -carcinoma, -sarcoma or -blastoma as a suffix, with the Latin or Greek word for the organ of origin as the root. For instance, a cancer of the liver is called hepatocarcinoma; a cancer of the fat cells is called liposarcoma. For common cancers, the English organ name is used. For instance, the most common type of breast cancer is called ductal carcinoma of the breast or mammary ductal carcinoma. Here, the adjective ductal refers to the appearance of the cancer under the microscope, resembling

normal breast ducts.

Benign tumors (which are not cancers) are named using -oma as a suffix with the organ name as the root. For instance, a benign tumor of the smooth muscle of the uterus is called leiomyoma (the common name of this frequent tumor is fibroid). Unfortunately, some cancers also use the -oma suffix, examples being melanoma and seminoma.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of cancer metastasis depend on the location of the tumor.

Roughly, cancer symptoms can be divided into three groups:

- Local symptoms: unusual lumps or swelling (tumor), hemorrhage (bleeding), pain and/or ulceration. Compression of surrounding tissues may cause symptoms such as jaundice (yellowing the eyes and skin).

- Symptoms of metastasis (spreading): enlarged lymph nodes, cough and hemoptysis, hepatomegaly (enlarged liver), bone pain, fracture of affected bones and neurological symptoms. Although advanced cancer may cause pain, it is often not the first symptom.

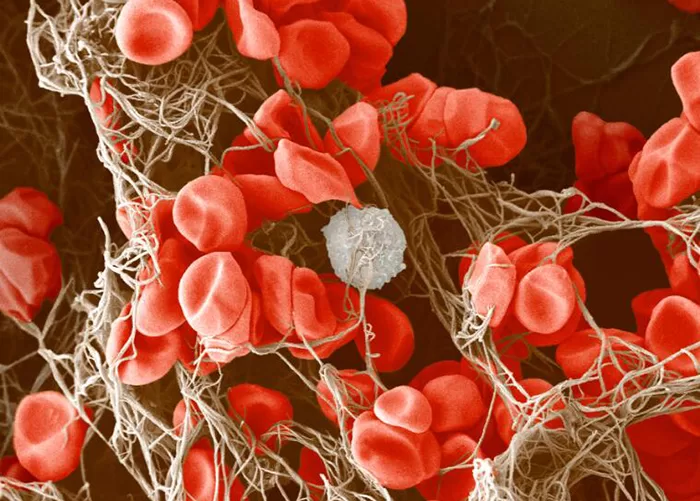

- Systemic symptoms: weight loss, poor appetite, fatigue and cachexia (wasting), excessive sweating night sweats), anemia and specific paraneoplastic phenomena, i.e. specific conditions that are due to an active cancer, such as thrombosis> or hormonal changes.

Every symptom in the above list can be caused by a variety of conditions (a list of which is referred to as the differential diagnosis). Cancer may be a common or uncommon cause of each item.

Causes

Cancer is a diverse class of diseases which differ widely in their causes and biology. Any organism, even plants, can acquire cancer. Nearly all known cancers arise gradually, as errors build up in the cancer cell and its progeny mechanisms section for common types of errors).

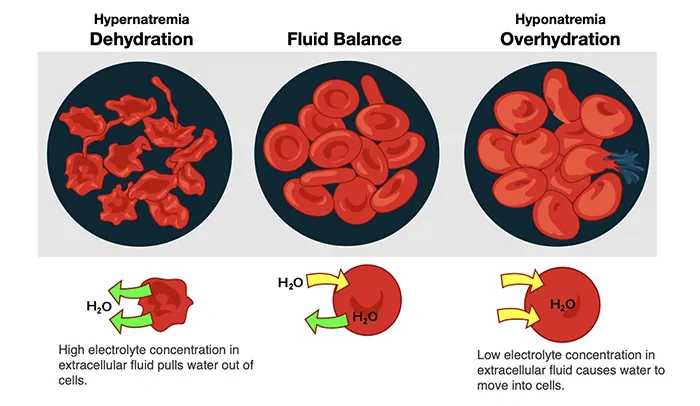

Anything which replicates (our cells) will probabilistically suffer from errors (mutations). Unless error correction and prevention is properly carried out, the errors will survive, and might be passed along to daughter cells. Normally, the body safeguards against cancer via numerous methods, such as: apoptosis, helper molecules (some DNA polymerases), possibly senescence, etc. However these error-correction methods often fail in small ways, especially in environments that make errors more likely to arise and propagate. For example, such environments can include the presence of disruptive substances called carcinogens, or periodic injury (physical, heat, etc.), or environments that cells did not evolve to withstand, such as hypoxia[5] . Cancer is thus a progressive disease, and these progressive errors slowly accumulate until a cell begins to act contrary to its function in the organism.

The errors which cause cancer are often self-amplifying, eventually compounding at an exponential rate. For example:

- A mutation in the error-correcting machinery of a cell might cause that cell and its children to accumulate errors more rapidly

- A mutation in signaling (endocrine) machinery of the cell can send error-causing signals to nearby cells

- A mutation might cause cells to become neoplastic, causing them to migrate and disrupt more healthy cells

- A mutation may cause the cell to become immortal telomeres, causing them to disrupt healthy cells forever

Thus cancer often explodes in something akin to a chain reaction caused by a few errors, which compound into more severe errors. Errors which produce more errors are effectively the root cause of cancer, and also the reason that cancer is so hard to treat: even if there were

10,000,000,000 cancerous cells and one killed all but 10 of those cells, those cells (and other error-prone precancerous cells) could still self-replicate or send error-causing signals to other cells, starting the process over again. This rebellion-like scenario is an undesirable survival of the fittest, where the driving forces of itself work against the body’s design and enforcement of order. In fact, once cancer has begun to develop, this same force continues to drive the progression of cancer towards more invasive stages, and is called clonal evolution.

Research about cancer causes often falls into the following categories:

- Agents (e.g. viruses) and events (e.g. mutations) which cause or facilitate genetic changes in cells destined to become cancer.

- The precise nature of the genetic damage, and the genes which are affected by it.

- The consequences of those genetic changes on the biology of the cell, both in generating the defining properties of a cancer cell, and

in facilitating additional genetic events which lead to further progression of the cancer.

Mutation: chemical carcinogens

The incidence of lung cancer is highly correlated with smoking. Source:NIH.

Cancer pathogenesis is traceable back to DNA mutations that impact cell growth and metastasis. Substances that cause DNA mutations

are known as mutagens, and mutagens that cause cancers are known as carcinogens. Particular substances have been linked to specific types

of cancer. Tobacco smoking is associated with many forms of cancer, and causes 90% of lung cancer. Prolonged exposure to asbestos fibers is associated with mesothelioma.

Many mutagens are also carcinogens, but some carcinogens are not mutagens. Alcohol is an example of a chemical carcinogen that is not a mutagen. Such chemicals may promote cancers through stimulating the rate of cell division. Faster rates of replication leaves less time for repair enzymes to repair damaged DNA during DNA replication, increasing the likelihood of a mutation.

Decades of research has demonstrated the link between tobacco use and cancer in the lung, larynx, head, neck, stomach, bladder, kidney, oesophagus and pancreas. Tobacco smoke contains over fifty known carcinogens, including nitrosamines and. Tobacco is responsible for about one in three of all cancer deaths in the developed world, and about one in five worldwide. Indeed, lung cancer death rates in the United States have mirrored smoking patterns, with increases in smoking followed by dramatic increases in lung cancer death rates and, more recently, decreases in smoking followed by decreases in lung cancer death rates in men. However, the numbers of smokers worldwide is still rising, leading to what some organizations have described as the tobacco epidemic.

Mutation: ionizing radiation

Sources of ionizing radiation, such as radon gas, can cause cancer. Prolonged exposure to ultraviolet radiation from the sun can lead to melanoma> and other skin malignancies. It is estimated that 2% of future cancers will be due to current CT scans.

Non-ionizing radio frequency radiation from mobile phones and other similar RF sources has also been proposed as a cause of cancer, but there is currently little established evidence of such a link.

Viral or bacterial infection

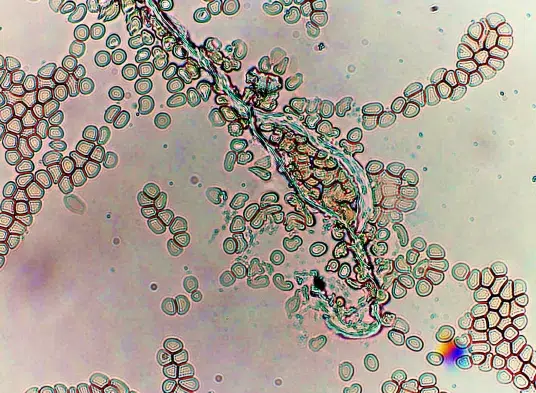

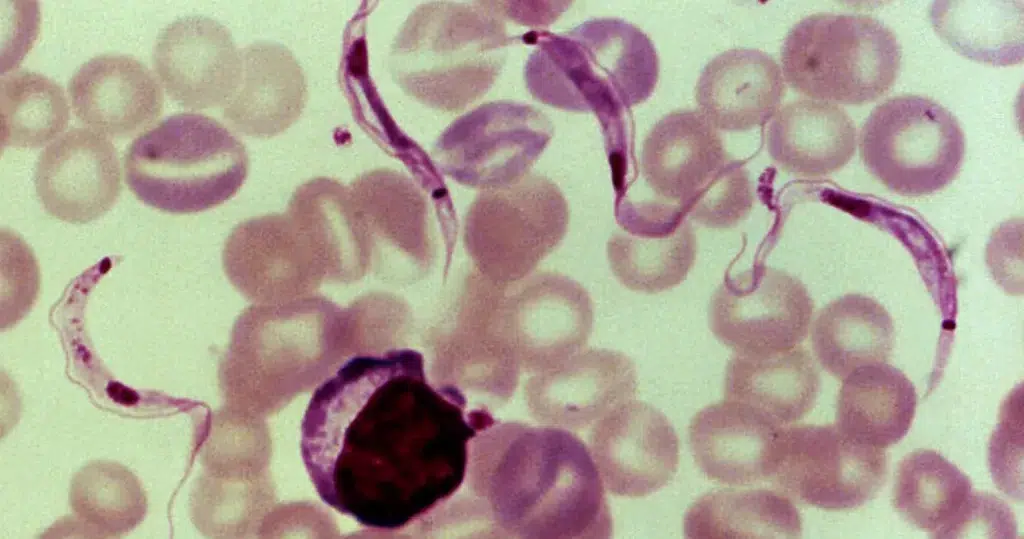

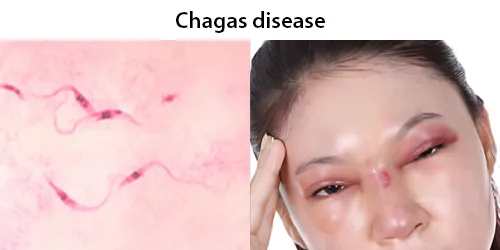

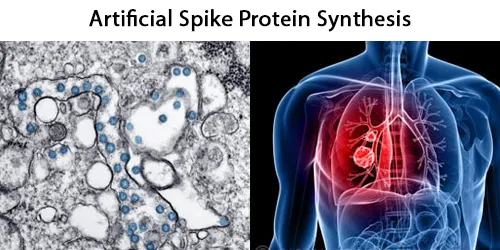

Some cancers can be caused by infection with pathogens. Many cancers originate from a viral infection; this is especially true in animals such as birds, but also in humans, as viruses are responsible for 15% of human cancers worldwide. The main viruses associated with human cancers are human papillomavirus, hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus, Epstein-Barr virus, and human T-lymphotropic virus. Experimental and epidemiological data imply a causative role for viruses and they appear to be the second most important risk factor for cancer development in humans, exceeded only by tobacco usage. The mode of virally-induced tumors can be divided into two, acutely-transforming or slowly-transforming. In acutely transforming viruses, the virus carries an overactive oncogene called viral-oncogene (v-onc), and the infected cell is

transformed as soon as v-onc is expressed. In contrast, in slowly-transforming viruses, the virus genome is inserts near a proto-oncogene in the host genome. The viral or other transcription regulation elements then cause overexpression of that proto-oncogene. This induces uncontrolled cell division. Because the site of insertion is not specific to proto-oncogenes and the chance of insertion near any proto-oncogene is low, slowly-transforming viruses will cause tumors much longer after infection than the acutely-transforming viruses.

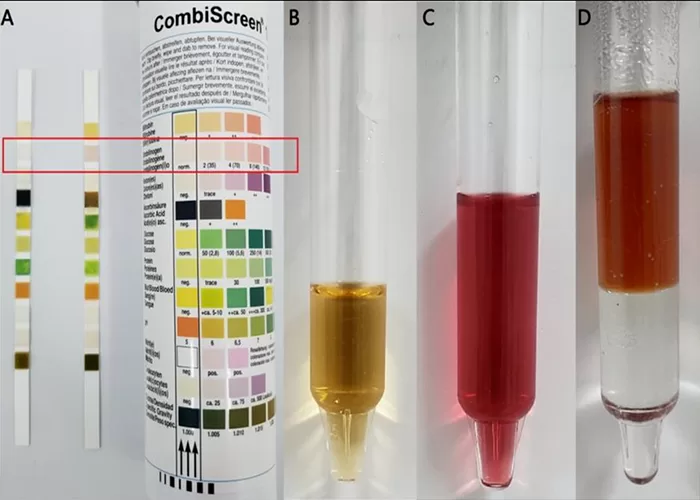

Hepatitis viruses, including hepatitis B and hepatitis C, can induce a chronic viral infection that leads to liver cancer in 0.47% of hepatitis B patients per year (especially in Asia, less so in North America), and in 1.4% of hepatitis C carriers per year. Liver cirrhosis, whether from chronic viral hepatitis infection or alcoholism, is associated with the development of liver cancer, and the combination of cirrhosis and viral hepatitis presents the highest risk of liver cancer development. Worldwide, liver cancer is one of the most common, and most deadly, cancers due to a huge burden of viral hepatitis transmission and disease.

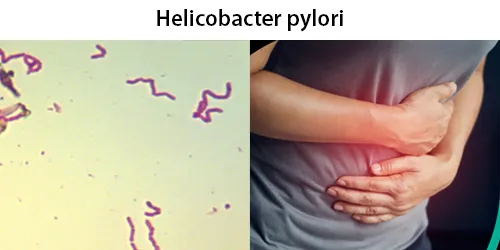

In addition to viruses, researchers have noted a connection between bacteria and certain cancers. The most prominent example is the link between chronic infection of the wall of the stomach with Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Although only a minority of those infected with Helicobacter go on to develop cancer, since this pathogen is quite common it is probably responsible for the majority of these cancers.

Hormonal imbalances

Some hormones can act in a similar manner to non-mutagenic carcinogens in that they may stimulate excessive cell growth. A well-established example is the role of hyperestrogenic states in promoting endometrial cancer.

Immune system dysfunction

HIV is associated with a number of malignancies, including Kaposi’s sarcoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and HPV-associated malignancies such as anal cancer and cervical cancer. AIDS-defining illnesses have long included these diagnoses. The increased incidence of malignancies in HIV patients points to the breakdown of immune surveillance as a possible etiology of cancer. Certain other immune deficiency states common variable immunodeficiency and IgA deficiency are also associated with increased risk of malignancy.

Glossary

Further information: List of oncology-related terms

The following closely related terms may be used to designate abnormal growths:

- Tumor or tumour: originally, it meant any abnormal swelling, lump or mass. In current English, however, the word tumor has become synonymous with neoplasm, specifically solid neoplasm. Note that some neoplasms, such as leukemia, do not form tumors.

- Neoplasm: the scientific term to describe an abnormal proliferation of genetically altered cells.

Neoplasms can be benign or malignant:- Malignant neoplasm or malignant tumor: synonymous with cancer.

- Benign neoplasm or : a tumor (solid neoplasm) that stops growing by itself, does not invade other tissues and does not form metastases.

- Invasive tumor is another synonym of cancer. The name refers to invasion of surrounding tissues.

- Pre-malignancy, pre-cancer or non-invasive tumor: A neoplasm that is not invasive but has the potential to progress to cancer (become invasive) if left untreated. These lesions are, in order of increasing potential for cancer, atypia, dysplasia and carcinoma in situ.

The following terms can be used to describe a cancer:

- Screening: a test done on healthy people to detect tumors before they become apparent. A mammogram is a screening test.

- Diagnosis: the confirmation of the cancerous nature of a lump. This usually requires a biopsy or removal of the tumor by surgery, followed by examination by a pathologist.

- Surgical excision: the removal of a tumor by a surgeon.

- Surgical margins: the evaluation by a pathologist of the edges of the tissue removed by the surgeon to determine if the

tumor was removed completely (“negative margins”) or if tumor was left

behind (“positive margins”).

- Surgical margins: the evaluation by a pathologist of the edges of the tissue removed by the surgeon to determine if the

- Grade: a number (usually on a scale of 3) established by a pathologist to describe the degree of resemblance of the tumor to the surrounding benign tissue.

- Stage: a number (usually on a scale of 4) established by the oncologist to describe the degree of invasion of the body by the tumor.

- Recurrence: new tumors that appear at the site of the original tumor after surgery.

- Metastasis: new tumors that appear far from the original tumor.

- Median survival time: a period of time, often measured in months or years, over which 50% of the cancer patients are expected to be alive.

- Transformation: the concept that a low-grade tumor transforms to a high-grade tumor over time. Example: Richter’s transformation.

- Chemotherapy: treatment with drugs.

- Radiation therapy: treatment with radiations.

- Adjuvant therapy: treatment, either chemotherapy or radiation therapy, given after surgery to kill the remaining cancer cells.

- Prognosis: the probability of cure after the therapy. It is usually expressed as a probability of survival five years after diagnosis. Alternatively, it can be expressed as the number of years when 50% of the patients are still alive. Both numbers are derived from statistics accumulated with hundreds of similar patients to give a Kaplan-Meier curve.

- Cure: A cancer patient is “cured” if they live past the time by which 95% of treated patients live after the date of their diagnosis of cancer. This period varies among different types of cancer; for example, in the case of Hodgkin’s disease this period of time is 10 years, whereas for Burkitt’s lymphoma this period would be 1 year. The phrase “cure” used in oncology is based upon the statistical concept of a median survival time and disease-free median survival time.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

All hyperlinks, graphics, and references have been deleted from the original article for inclusion of this page in this web site.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cancer